9.3

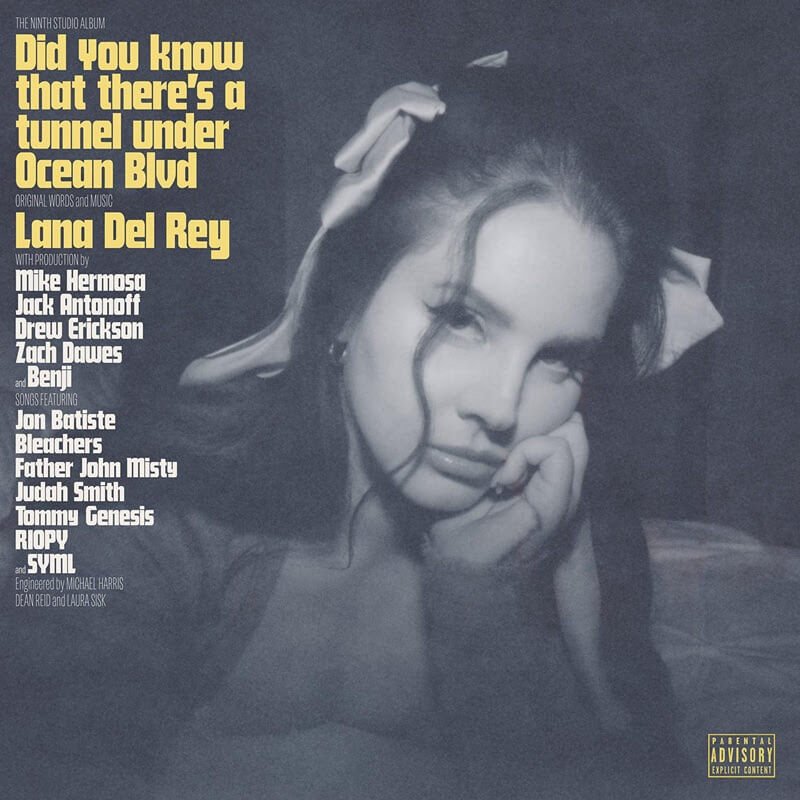

Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd

Lana Del Rey

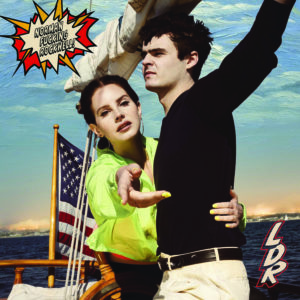

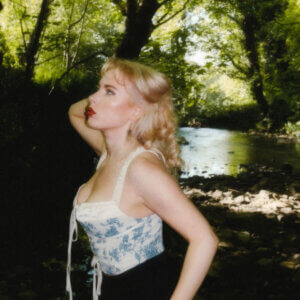

It is extraordinarily difficult to refute one well known blog’s claim earlier this month that Lana Del Rey is the greatest American singer-songwriter of the twenty-first century. After a career beginning with a rocky critical response, her string of albums after 2019’s career-defining Norman Fucking Rockwell! have been gorgeous, orchestral baroque pop offerings that posited her as the Ottessa Moshfegh of music: the best conduit for offering meditations on life when it sucks.

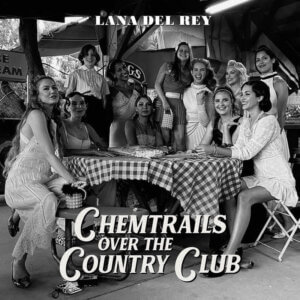

Her extraordinary duo of albums beginning with NFR! and ending with 2021’s Chemtrails Over the Country Club were packed with emotive, masterful ballads placed among sweeping grandiose statements — the best of both categories being that which encompassed both styles (“The Greatest”, “Mariners Apartment Complex”, “White Dress”, each album’s title tracks). Topics ranged from Sylvia Plath to Kanye West to Sublime, but for her most recent offering, Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd, she turns almost entirely to herself, her past, and her place as an artist and person.

Its first hints appeared in an interview last May, where Del Rey admitted the upcoming project was more “wordy”, “conversational”, where she would create songs by opening up the voice notes app on her phone and rambling. These are most clear in the album’s deepest part, right in the middle of the tracklist, “Kintsugi” and “Fingertips”, a devastating duo about grief, suicide, and healing. “Kintsugi” is more structured, building around the Japanese technique of the same name where broken pottery is mended by gluing the parts together with gold adhesive, the principle being to incorporate the history of the object and its broken parts in its present form. Lana compares this to her own feelings, and says, “It’s just that I don’t trust myself with my heart / But I’ve had to let it break a little more / “‘Cause that’s what they say it’s for,” eventually realizing that “That’s how the light shines in,” a motif repeated in a duet with Father John Misty later down the line.

In contrast, “Fingertips” tumbles on, a 6-minute ballad with a haunting piano backing and fluctuating vocal performance. “It definitely explains everything,” she said for Rolling Stone UK, and by ‘everything’, she means the entire story of her life. The main focus is her uncle, David Grant, who committed suicide at the Rocky Mountain National Park in Colorado in 2016. “To get to you, save you, if I take my life / Find your astral body, put it into my arms,” she reminisces about her late uncle. She recounts an experience when she was fifteen, seemingly in the middle of a suicide attempt, when neighbors rescued her. “Sometimes it’s just not your time,” she admits. There are a plentiful amount of gorgeous and heartbreaking reflections on her childhood; asking her mother (the word, when it appears in the song, is censored) why she thought Lana would end up institutions, psychiatric drugs she takes (“It wasn’t my idea, the cocktail of things that twist neurons inside / But without them, I’d die”), or the reckoning of grief, asking herself if she’ll outlast her siblings or telomeres.

The album that houses these two dark songs is mostly positive, still talking about hard lessons in leaving, memories, and death, but its reflections never loom as difficult questions rather than things learned and lived through. Its first two songs touch on memory the most, with the title track about the legacy Del Rey will leave as an artist and human. “The Grants” is one of her most beautiful opening tracks yet, closing in on the memories she’ll take with her when she dies: her sister’s child, her grandmother’s last smile. She reflects on something her pastor said, being that when you die, all you take are your memories. “I’m gonna take mine of you with me,” she promises, before a heavenly outro.

This gratitude comes out in other places as well — on “Kintsugi”, when thinking about those who will stay until the very end of one’s life, she sings, “You think about who would be with you / And then there’s Donoghue”, alluding to her boyfriend by name (the same one she begs on the title track, “Fuck me to death, love me until I love myself”). She mentions him again on “Peppers”, where daily activities become a means of romance: “My boyfriend tested positive for COVID, it don’t matter / We’ve been kissing, so whatever he has, I have.” The album’s most tender moment, though, might be “Margaret”, a story telling the love of longtime collaborator Jack Antonoff, who is featured on the song. They sing of a love so powerful it’s immediately visible, its fate already decided, simply waiting for the two to realize. “When you know, you know”, she sings, “The soul that you bring to the table / The one that makes me sing in a minor key.”

Del Rey’s wonder comes from when she mixes stark, serious observations about the world amidst peeks of humor and light. This album, unlike any other, showcases her personality, the friend of yours whose humor might be a little too dark. On standout track “A&W”, she sings a diss-track to an ex-boyfriend who only used her for weed, ending with the deliciously petty refrain of “Your mom called, I told her, ‘you’re fucking up big time.’” All this proceeds a reflection of rape culture, how women’s bodies are dissected by the media, and her use of sex in order to get away from herself. “Did you know a singer can still be / Looking like a sidepiece at thirty-three?” she asks of herself. On the bizarre “Peppers”, the rapper Tommy Genesis sings in the album’s catchiest moment, “Hands on your knees, I’m Angelina Jolie”, the reference not being immediately clear, but so funny, it doesn’t particularly matter. “That’s why they call me ‘Lanita’,” she sings on the closer (no one calls her that), and on “Sweet”, a gorgeous piano ballad describing her individuality and asking her partner their future plans, she says, “I’m a different kind of woman / If you want some basic bitch, go down to the Beverly Center and find her.”

Ocean Blvd isn’t without fault, though, and its most common (and valid criticism) is its length. At 77 minutes, it’s her longest record yet, and with several songs hovering around 5-6 minutes, it’s not necessarily an easy listen. Two interludes bookend “A&W”, the first of which is a recording from a preaching sermon by Judah Smith, who is so passionate about the danger of lust in today’s society you’d think he was a student of Jenny Fields from The World According to Garp. Further down in the tracklist, too, there are some pretty obvious cuts: “Fishtail” has clever observations about the romanticization of depression and other mental illnesses, but its odd autotune doesn’t help its message. The closing track, “Taco Truck x VB”, features the long-awaited heavier version of fan-favorite song “Venice Bitch”, but its rendition isn’t drastically different, and leaves the feeling that a stronger closer would have been “Let The Light In” or “Margaret.”

Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd is a magnum opus of sorts — not immediately gratifying as Norman Fucking Rockwell! but packed with the observation and reflection that makes it one of her deepest and most personal albums to date. Mixed with interesting production amongst beautiful folk cuts, Lana dissects her history with a blade so sharp and a mind so keen it makes sense she emerges a little broken. “Doin’ the hard stuff, I’m doin’ my time,” she admits on the opener, surrounded by a choir, ready to dig into everything that made her the woman she is today — the beautiful and the illicit. But, as they say, that’s how the light shines in.

Order by Did you know that there’s a tunnel under Ocean Blvd by Lanna Del Rey HERE

Latest Reviews

Tracks

Related Albums

Related News

Advertisement

Looking for something new to listen to?

Sign up to our all-new newsletter for top-notch reviews, news, videos and playlists.