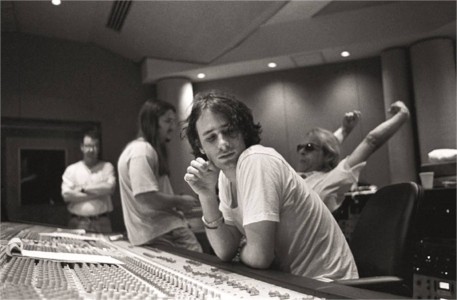

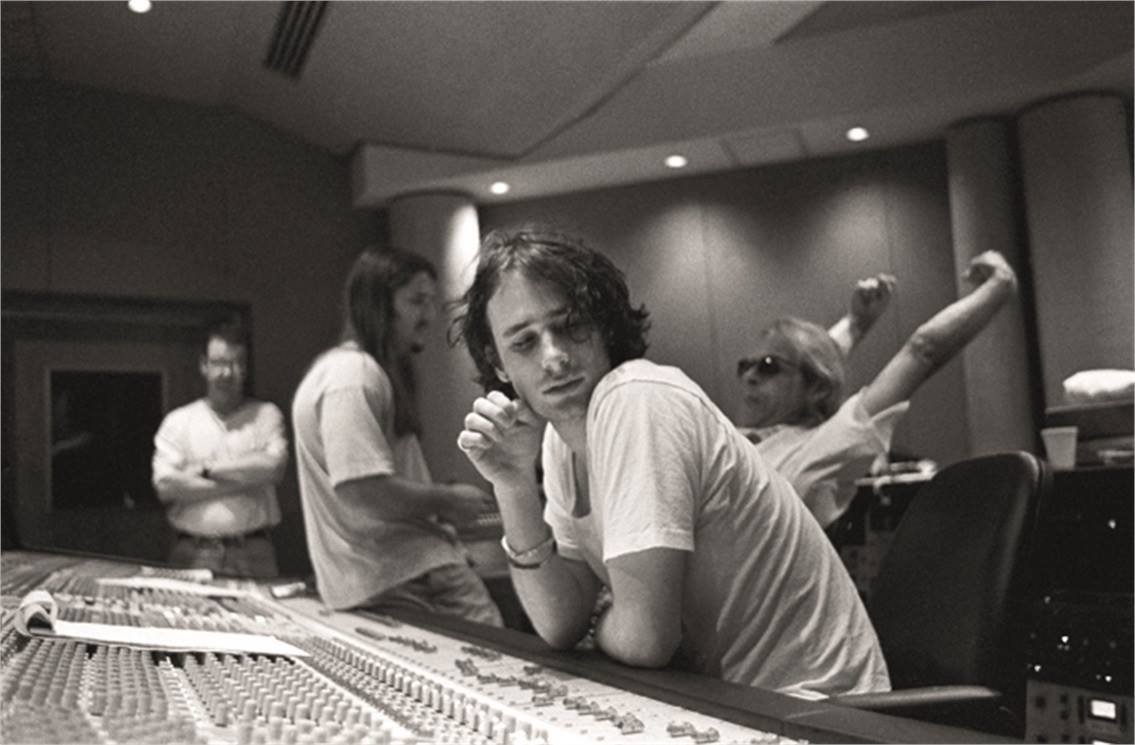

JEFF Buckley’s first studio sessions revealed

In February 1993, in a New York City recording studio, sat two men, Steve Berkowitz, A&R for Columbia Records and Jeff Buckley, about to begin recording sessions for his first record for the label. Behind the glass windowpane at Shelter Island Sound Studios was producer/engineer Steve Addabbo. It was the first time Buckley recorded for Columbia and Berkowitz wanted to make sure the musician was comfortable and allotted a few days of studio time for Buckley to play with no pretense.

“It’s me, at this little table,” Berkowitz recalls, “there’s him, he’s facing the glass of the engineer behind the glass. I thought maybe we could have some coffee, tell some jokes, loosen up a little bit.”

These low-pressure recordings, just preceding those that appear on his 1994 album Grace, which include covers of Bob Dylan’s “Just Like A Woman” and Sly and the Family Stone’s “Everyday People,” were never publicly released. They existed in the Sony Music archives where, until recently, they sat undisturbed for more than 20 years.

However, in researching for the 20th anniversary edition of Grace, these tracks were unearthed and thus whittled down to ten songs—eight covers and two originals including the first-ever studio recording of “Grace” and a never-before-heard track, “Dream of You and I”—for You and I, the discovered early studio sessions, out March 11 on Columbia/Legacy Recordings.

The intimate and expressive performances show Buckley’s ability to make each song his own, a personal encounter with music and experience. Regardless of genre or age, Buckley puts bits of himself in each song, reimagining each through only vocals and guitar.

Berkowitz remembers it all fondly: the experience, the time he spent with Buckley and the music that resulted from those days. Ahead of You and I’s release, he spoke with us about the magic of the early Buckley studio sessions.

Northern Transmissions: Tell us about the time of these recordings.

Steve Berkowitz: It was wonderful and dreamlike now. Jeff was clearly magnificently talented and could go in many directions. I’ve barely met a musician who was as talented and good at so many different things. After we’d met and known each other a year or so, there were many labels interested and we were lucky enough to sign him at Columbia. Then it became time to make an album. It was still Jeff—he didn’t have Ricky the bass player, he didn’t have Matt the drummer. It was him and his Telecaster trying to think about what record he might make. I’m not sure he felt like he was in a huge hurry, but after a number of months, the company sure was interested in making a record.

Jeff could do so many things, I think the hardest thing about deciding what Jeff Buckley he was going to be when he made a first record was for anything he chose, he’d give up something else—or several something else-s. Whether it was prog, or blues, or jazz, or reggae, or mainstream stuff, he could play so many things. The whole idea here was, only Jeff was going to decide what it was he was going to do. I suggested that we maybe go into the studio and just record as much as he could, think of recording for one or two or three days. At the end of that, if there were a couple of particular things that he really liked, maybe that was the beginning of making a full album.

NT: So it was kind of like a warm up session.

SB: The thing about Jeff though is that he only made music. I can’t say that he made demos. But in this case, it was “let’s go and record.” At the very beginning, he also had some trepidation of signing with the big major label. Here he is on the Lower East Side, with his friends and struggling musicians and artists and poets and actors—and in some ways you have to beware of the big record company. He didn’t have to worry about that because he had a contract that said that he was in control of what would come out.

But we start this first day in February ’93, and he just realizes, “Geeze, I’m on Columbia Records’ dime now. This is kind of tense. I’m sort of recording for the man now.” Part of the exercise that I hoped was that he would take it easy and just start to play because he was going to control what he did anyway.

NT: Did he go into it picking these songs ahead of time?

SB: When we went in on the first day, we didn’t know whether it was one or two or three days. I think he had a pretty good idea of a dozen or so songs that he wanted to play. We got to the middle of the afternoon, and I’m still literally in the room with him, the recording room. I was trying to make it natural, like you were in somebody’s living room just singing a song.

After he’d gone through a dozen or so songs, he goes, “Well maybe that’s about it.” And I went, “Come on. You know every song ever written. We can keep going.” I was like, “Do you know any Eisley Brothers songs? Curtis Mayfield? What about Sly?” And he starts slipping on his guitar and singing [“Everyday People”]. He didn’t really remember all the words; somehow the words appear in the studio, which you can hear in the tapes. About the third take of “Everyday People,” Jeff closed his eyes, opened up his chest a bit more and really let loose. That version of “Everyday People” is what you hear on this record. It was done that day, after not thinking about it, it just came out of him. As he closed his eyes and his voice really started to open up, he was much more relaxed and ready to start doing more of what ended up happening on day two and three, which is mostly what’s on this record You and I. He kind of got over those early jitters and did what he always did: internalize the music and then have it emit out of him and share it with you, with me, with the room, with the microphone. He didn’t play gigs—he made music.

NT: What do you think these recordings say about Jeff at the time, about music at the time?

SB: I think there’s one, two, three, four chapters of the all-too-brief Jeff Buckley recordings for Columbia Records. You’ve heard sections two, three and four, which are Sin-é, the album Grace and the demos and the sketches from My Sweetheart the Drunk. This is chapter one, which, until now hasn’t been out. It’s him and the way that it was in the clubs and he’s just starting to gain confidence in himself. He didn’t just get good when we went in to do this. He was already good. He just needed to figure out how to bring it—and this is an important stage captured.

NT: He has an ability to make others’ songs his own.

SB: That was one of the things: he could sing everything. From Judy Garland to Led Zepplin to Bob Dylan and Miles Davis, he could figure out all of this music. He didn’t really copy anybody—he wasn’t a cover act. This whole idea of him internalizing all of the music in a spiritual way, emitting it out there, that’s why they all become so personal. He’s not doing it to perform for you, to dance around—he’s doing it to make music and bring you into it.

NT: What were those moments in the studio that were memorable?

SB: I was blessed just hanging around with Jeff a lot. He’d only play good and better than good. In the early days, he would start to play “Hallelujah,” if he misspoke on a verse, he would just stop and say “Sorry, wrong words. If I’m going to bother to do it, I should do it right.” He had respect for the music, he had respect for himself, he had respect for the people that he was with in the room, the people in the audience were his friends. And he was very serious about it.

Interview by Allie Volpe

Latest Reviews

Tracks

Advertisement

Looking for something new to listen to?

Sign up to our all-new newsletter for top-notch reviews, news, videos and playlists.