Why music journalism still matters in 2019

“They’ll buy you drinks, you’ll meet girls, they’ll try to fly you places for free, offer you drugs… I know. It sounds great. But they are not your friends.”

You may remember these as words of advice given by Lester Bangs to young, aspiring rock critic William Miller in Almost Famous as caution not to get too close to rock stars, and it stands in 2019 as a very literal (perhaps excessively so) description of the modern dynamic between music journalists and artists – especially in our social media-driven landscape, where the gap between the two is much closer than in decades past.

The list of artists firing back at critics online is an extensive one within this decade alone – Ariana Grande, Nicki Minaj, of Montreal’s Kevin Barnes, CHVRCHES, Ice-T, and the Naked and Famous are but a few examples. In particular, Barnes wrote a hilariously scathing annotated rebuttal on his former Tumblr account to Pitchfork’s review of of Montreal’s 2010 album False Priest, even though its score was a decent 6.7/10.

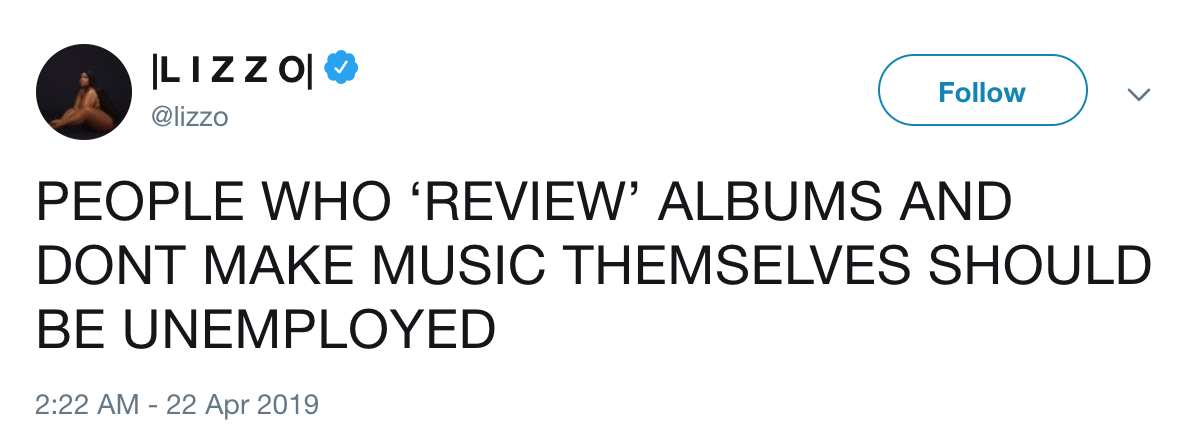

However, a since-deleted tweet in late April from fast-rising rapper/singer Lizzo set off a whole new debate as to the very purpose of music criticism.

Lizzo’s tweet in question was in response to Pitchfork’s review of her major label debut album, Cuz I Love You, in which writer Rawiya Kameir described the album as being “burdened with overwrought production, awkward turns of phrase, and ham-handed rapping,” and that the music “can feel like a means to a greater end.”

Though it’s fairly easy to see why Lizzo would be upset by parts of the review – comparisons made by the writer between her and Meghan Trainor, Natasha Bedingfield and the Black Eyed Peas are reductive for an artist of her talent level, regardless of context – the review’s score was ultimately a 6.5/10; a slightly underwhelming critique in a sea of otherwise extremely positive ones for her LP.

A rapper, singer, and flautist, Lizzo is an undeniable talent that has already played Coachella, performed on Jimmy Kimmel Live!, and worked with the late Prince in 2014, and it’s entirely possible she was disappointed the review came from a publication known for helping some newer artists’ steadily burgeoning careers sink or swim based partially on their review scores – or perhaps she mainly took issue with the tone of the review itself. However, to suggest that music journalists should be slumming it out in the streets on the sheer basis of them analyzing music in written words without creating or making music themselves is a narrow-minded – and at best, outdated – argument. That said, it also begs the question: “What is the role of the music journalist in 2019?”

Toronto Star music critic Ben Rayner admits he’s experienced his share of direct responses from both artists (Cher, Eddie Van Halen, Backstreet Boys’ Kevin Richardson) and fans (Guns ’N’ Roses, Yanni, Neil Young) over reviews he’s written. Though he tries to “put [himself] in the head” of music fans as well as through being someone who plays music and understands music theory, he doesn’t care about the music critic vs. actual musician argument.

“I would’ve loved to be a musician for a living, but my love of music led in me in this direction. I still like playing music, but it was never going to be a career,” he says. “I have friends who have never touched a drum kit or a guitar in their lives, but they’re just so deep into [it] – it’s a whole other level of nerdy. People who don’t even want to go to shows, right? They just want to stay [home] with their records. Everybody’s got their own approach to it. As long as you’re honest about it, it doesn’t really matter.”

Rock publications, or at least the ones many of us grew up with, are gradually dying out: once-iconic magazines like NME and SPIN have ceased publishing their print editions and pivoted mainly to online content, while Pitchfork’s own print edition, The Pitchfork Review, folded in 2016. In particular, NME’s average weekly circulation during the second half of 2014 was only about 14,000 before being made into a free magazine the following year. While Rolling Stone remains by far the most heavily circulated music magazine in the United States as of 2017 (at just under 1.5 million), the next-highest music publication on the list is Music Alive! – an educational music magazine for schoolchildren – with a circulation of only 500,000, while longtime emo/pop punk magazine Alternative Press ranks third with just under 300,000.

Even for well-known critics who do happen to be practitioners of the very art forms they’re critiquing, they don’t necessarily find much success in their moonlighting. Though Roger Ebert dabbled in screenwriting, Lester Bangs himself was an occasional musician, and popular modern-day YouTube music critic Anthony Fantano – known for his YouTube channel theneedledrop – plays bass and produces instrumental hip hop as his moustachioed alter ego Cal Chuchesta, all three remain far more known for analyzing their respective art forms as opposed to actively making art themselves.

Not only are the critics who also happen to dabble in their chosen art form better known for critiquing the art than contributing to it, being a musician arguably isn’t a prerequisite the way having a critical and analytical mindset when it comes to music is. Take, for example, Montreal-based freelance music journalist Erik Leijon, who admits he “can’t carry a tune,” and got much of his music education from listening to music around the house growing up, as well as watching MuchMusic and its recently-deceased French-language sister station MusiquePlus – crediting the latter’s show “Le cimetière des CD” as being where he learned a lot about review writing. As far as artists responding to critics is concerned, he welcomes the dialogue resulting from music reviews, and invites criticism for his own work.

“I’m not somebody who holds the position of ‘critic’ as some sanctified, deified thing,” says the Montreal Gazette and Cult MTL writer. “If you’re going to criticize an artist, you’ve got to be willing to take it back. I think the worst thing either side could do is invalidate the other’s opinion, or say ‘You can’t say this,’ or ‘You can’t say that.’”

While writing about music may not often be a particularly lucrative endeavour, some music critics have found success doing album reviews, video essays, and other music-related video content on YouTube – channels like ARTV, Dead End Hip Hop, Polyphonic and Middle 8 being among the more prominent examples. However, the most famous one is arguably Fantano, who has close to 2 million subscribers on theneedledrop, and with viewers having spent an impressive average of four minutes per video with his content as of 2016. Though there are exceptions to the rule, blogs and websites don’t seem to command the same sort of attention from music fans they used to, at least not compared to audiovisual formats. In other words, it’s entirely possible music critics and publications may have to increasingly shift their focus toward video content to publish their reviews.

Vancouver-based musician Jody Glenham has been on both sides of the coin: not only does she have a career as a musician in addition to working three jobs, she has contributed album reviews to Western Canadian monthly publication BeatRoute. In her view, while being able to create music is an asset for review-writing, it’s not a requirement compared to “good taste and a valid opinion.” However, Glenham also isn’t sure there are many who still enjoy discovering artists through publications and word-of-mouth.

“People are busy in their everyday lives,” she says. “For example, Pitchfork in its heyday was how everyone found out about their new music. Now, there’s Spotify and Apple Music curating playlists – it’s kind of like there have been more gatekeepers of how people are finding out about new bands and new artists. [But] I think music journalism is still an important aspect of it.”

Furthermore, with Spotify and Apple Music seemingly dominating modern music consumption from the consumer’s perspective (100 million and 50 million paid subscribers worldwide, respectively), there is no longer much of a desire to essentially be force fed new music via radio or MTV (or MuchMusic, for all you Canucks out there). A whole, wide open world of music is available at our fingertips, and music journalists can provide well thought-out essays on music to help make sifting through the literal and figurative noise easier for readers – though the listener’s opinion of the music itself is ultimately up to them, as music is a highly subjective and visceral art form.

Though there’s been some great online music journalism published in recent years, it nonetheless appears to have lost some of its influence since the aughts – the aforementioned Pitchfork has been credited for helping to break artists like Arcade Fire, Bon Iver, Broken Social Scene and Sufjan Stevens, while blogs like Brooklyn Vegan, The Hype Machine, and Gorilla vs. Bear were also acting as popular sources for music discovery during that decade. However, YouTube and streaming services – particularly Spotify playlists – continue to dominate the landscape for music consumption and discovery – and in Leijon’s opinion, it takes away from the music writer’s work being seen by potential readers.

“If you trust a writer, you’re not even going to the website anymore. You’re just following them on social media, and they’re giving it all away for free. You’re not even clicking on the website anymore, which is that writer’s meal ticket,” he says. “I don’t blame anybody for doing that – there’s so much out there. It’s so easy to go on your Twitter, or Facebook feed, and watch all the opinions roll in. That’s all our brains have time to absorb, so that’s a perfect place to do it. Music websites and blogs are competing with that.”

Despite the gloomy-looking present and future of online music journalism, there’s reason to believe it still has its place in today’s musical climate, even if the way we engage with it has evolved just as the technological landscape has. In Rayner’s case, he began life at the Star while there were critics onboard for books, dance, jazz music and classical music, whereas nowadays there remains only him and a movie critic at the newspaper. Regardless, he still sees value in music journalism itself.

“Back in the day, you had a regular voice, the same person you could engage with every day, and there were only so many,” he says. “It’s someone you could use as a pivot for your own opinions. Like ‘This guy never likes horror movies, I like horror movies. I know I’m gonna like the new Pet Sematary.’ That’s the value in the multiplicity of voices.”

Words by Dave MacIntyre

Latest Reviews

Tracks

Advertisement

Looking for something new to listen to?

Sign up to our all-new newsletter for top-notch reviews, news, videos and playlists.