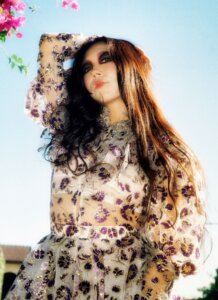

The Many Fascinating Interests Of SASAMI

Horror manifests in many ways on SASAMI’s sophomore album, Squeeze. Speaking with Northern Transmissions, the Los Angeles-based artist explains that she wanted the record to possess “a freaky haunted house” feeling akin to cult horror films like Hausu and Child’s Play. By pulling influence from nu metal groups like System of a Down on tracks like the raging “Skin a Rat,” she conjures the inescapable angst of turn-of-the-century teendom. More centrally, SASAMI made yōkai folklore figure the Nure-onna her avatar on Squeeze’s album cover, her likeness fantastically re-imagined as the snake-like “wet woman” that, according to legend, could “brutally destroy victims with her blood-sucking tongue.”

On the sonic side of things, while SASAMI had planned for her latest album to be front-to-back metal crushers, songwriting sessions during an artist residency in Seattle took the compositions in a more expansive direction. “No matter how heavy you want them to be, some songs want to be a slow pop song,” she explains.

As such, Squeeze takes a number of wonderfully seismic stylistic leaps. While pieces like “The Greatest” tap into the hypnotizing indie-pop immersion of her 2019 self-titled debut, the new record likewise bobs towards the skronked-out panic chords and confrontational double-kick drumming of metal (“Need It Work”), bright and buoyant folk bops (“Tried to Understand”), gloom-glazed orchestral work (“Feminine Water Turmoil”), and mechanized industrial-pop (“Say It”).

Speaking with Northern Transmissions, SASAMI delivered details on Squeeze’s fantastical reach; collaborating with a wide-range of folks from Vagabon, to the drummer of Megadeth, to her current backing band, Vermont metal unit Barishi; and more.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Northern Transmissions: It’s been a chaotic few years since you released your first album—the pandemic, mass protests, climate change, all that. This is paraphrasing the first song on Squeeze, but how much of that, if any, put you in a “skin-a-rat-mood”?

SASAMI: With anyone who’s making art during the pandemic, and this tumultuous time, I think there are varying ways you can go with it. You can either make something that’s happy—that can kind of turn the mood around and unsettle the darkness—or you can make something sad and be processing those internally heavy emotions. My thought was to delve deeper into the angry, frustrated, vengeful emotions that kind of come along with dealing with existence in this dark period.

NT: How much of this was written during your songwriting residency in Seattle?

S: So I went to this songwriting residency, which was only 10 days but it was in a cabin in the woods. I was intending to be more, you know, Joni Mitchell with my guitar—getting interested in nature, being Zen, and doing some songwriting—but the night before [I left], I had gone to see my friend Kyle’s hometown friend’s band Barishi play at Five Star Bar, which is this dive bar in downtown L.A. I was really moved by the double-kick pedal. I was already riding on a feeling of wanting to make a heavy record after touring my first album, so when I went to that show it locked in place that [I’d] tap into more of these metal elements.

NT: Sonically, songs like “Skin a Rat” and “Need It To Work” are big pivots from your debut. What’s your relationship with heavy music, in general? Did you grow up listening to metal?

S: I’ve gone through a lot of different phases with listening to metal, but in terms of this album I feel like I was connecting with a middle-school relationship with nu metal. I wanted to make an album that touched on feelings of drama and being extreme; I feel like there’s no time in your life that is more emotionally strained than middle school or high school. When I tapped into those memories of listening to this music, it kind of brought me to an angsty place. [But] this album is way less autobiographical, and way more about fantasy and creating emotional experiences.

[With] darker death metal or tech metal, to me it’s almost like a grim reaper with a knife, whereas System of a Down and Korn, it’s more like a Chucky doll—something that’s almost happy looking, like a clown with a knife. It’s a twisted kind of scary. I was looking for that kind of emotional palette for this album. I wanted it to feel like a freaky haunted house.

NT: Getting into a different kind of legend or iconography, how old were you when you were introduced to the concept of the Nure-onna?

S: My uncle on my mom’s side was an anime artist; I grew up around anime and yōkai folk tales. When I was building this album, I knew I wanted the album cover to be an avatar, as opposed to a very literal portrait. Being an Asian-looking feminine person, it just made sense to look to East Asian folklore for a character that I could connect with. Like, I don’t look like Barbie. It was just natural for me.

I was already doing a deep dive on my family’s history, and I was really inspired by Lady Snowblood, Hausu, and The Ring—all this Japanese horror film imagery. It all tied into a fantasy world that I was already clicked into. I was lucky enough to [connect with] Andrew Thomas Huang, who worked on the album cover. He draws a lot of Chinese Gods and deities—mystical characters—so it was already in his wheelhouse.

NT: What was it like for you to separate the art from the artist via that kind of an avatar?

S: With this album I was much more focused on eliciting some sort of emotional response from the listener, as opposed to having my own specific cathartic processing experience. It all comes from a place of fantasy, which is why I wanted the avatar to be something that’s not even possible in reality. I think that’s something that attracts me to metal, theatre, and ballet, where small adjustments change your framework completely. Like, you’re at a metal show and someone has paint on their face, and they’re screaming. All of a sudden you feel like you’re in this hell-pit instead of this dive bar in downtown L.A. I like that feeling of transportation.

I really wanted the album to feel like a space where people could let go of reality. When we have frustrations [in real-life], we have to process it in a way that’s dignified and kept together. You can’t just go around smashing other people’s cars or lighting fires. I think that art is a really great place for people to have that experience of processing their rage without injuring someone or causing harm.

NT: Metal is a big part of Squeeze, but there are also songs like “Make It Right” or “Try to Understand” that operate on a folkier wavelength. Were these songs written in stylistic chunks, or had it all flowed freeform, like the sequence of the album?

S: I have two parts of my brain. One is the songwriter, and the other part is the producer/arranger/orchestrator. Initially I wanted it all to be heavy rock, but by the time I entered the producer brain, I [had] to do justice to the songs. No matter how heavy you want them to be, some songs want to be a slow pop song. [But] it’s my job as an artist to make it cohesive. Certain musical elements like the slap bass and the heavy guitar chugs on “Call Me Home,” or the distorted guitar in “Feminine Water Turmoil” sonically tie it all together.

Also, I wanted there to be this feeling [where] there’s never that little voice in your head saying, “It’s going to be ok.” I didn’t want that perspective to be on the album. I wanted to lean into the negativity—spiraling anger and frustration. Songs like “Make It Right” or “Try to Understand,” even though they sound happier they still have a darkness to them.

NT: There are a number of collaborators across Squeeze. With respect to “Skin a Rat,” how did you manage to pull Megadeth drummer Dirk Verbueren’s number out of your back pocket?

S: I mean, that’s definitely just the internet—the era we live in where everyone is one internet connection away. That was the first session that I did for the album, at Ty Segall’s studio in Topanga. I’d sent [Dirk] the demos. He basically learned the drum parts that I wrote in Garageband, and came in and played them flawlessly. I wasn’t even sure that was technically possible. It was nerve-wracking to send him my demos. In the way that classical musicians have a certain pedagogy or craft—that kind of dedication—I feel like metal musicians are like that, too.

NT: How about the gang vocals on that song from Patti Harrison and Vagabon?

S: I actually sang and played some French horn on Laetitia’s last album [2019’s Vagabon], but it was the first time I had [her] on an album. After working with a lot of men on the instrumental tracks, I knew that I wanted to have more people [from] my community—literal voices—on the album. To me, that’s the missing link with a lot of the heavy rock music. It’s not really safe or targeted towards people of colour, or queer people. I wanted to make sure that it’s very clear that the music on Squeeze was accessible for those people. Also, it’s fun to work with my friends.

NT: How has it been to integrate these kinds of heavier songs into your live show?

S: I mean, it’s really full circle. Barishi is a band that I saw before I made the album, and now they’re my backing band. It’s amazing to have such a talented band bring these songs to life [with me]. It feels like we’re unstoppable when we’re out there.

NT: It’s awesome that you’ve got one upcoming stretch with Haim, and then another tour lined up with punk and hardcore bands like Zulu and Jigsaw Youth. You’re opening yourself up to a lot of musical worlds…

S: Part of it is just being alive during this time where people listen to playlists more than they listen to albums. We have this jumpy way of listening to music that spans so many genres. People are more open to different genres than they were in the past. I feel like a show is more fun when there’s a different kind of energy between the openers and [the headliner]. I’m excited that Haim is down to expose their listeners to the chaos that I’m toting around.

NT: After putting together this varied set of songs, and with respect to a line on the album’s closing “Not a Love Song,” has the idea of what constitutes a “beautiful, beautiful sound” changed for you?

S: That song is way less about human-made noise and more about nature. I think that so many of the songs on the first part of the album are about these very human concepts—experiences like love, not reciprocating love, not being communicated to, or systemic oppression. These things are all very human. But by the end of the album I wanted to blow it up, existentially, by thinking about our place within nature, and questioning why we have to take everything and centre it around us. Like, why does everything that sounds melodic have to be a love song?

And also, it’s kind of after-care. After putting such abrasive sounds together, I wanted to end in a way that’s more respectful to the listener—bringing us back to a homeostasis after bringing people’s blood pressure up.

NT: Not to be reductive on that point, but what comes to mind first, in terms of the most beautiful sound in nature?

S: There are so many. Right now I’m sitting outside and the wind is brushing the weeds together. I could easily be like, “that sounds like jazz brushes on a snare drum,” but it’s not. It’s just a beautiful brushing of weeds in the wind. Same thing with birds, or whale sounds, anything like that. Or we take the moon, which has nothing do to with humans, and say there’s a face on it. We have this sickening desire to centre ourselves within everything. So I guess my question at the end is, after talking about humanity for 30 minutes, “Where do we belong in the grander scheme of things? And is there more horror to be processed in that relationship?”

Pre-order Squeeze by SASAMI HERE

Latest Reviews

Tracks

Advertisement

Looking for something new to listen to?

Sign up to our all-new newsletter for top-notch reviews, news, videos and playlists.