Jonathan Holiff Interview

Charles Brownstein talks to Filmmaker Jonathan Holiff about his new film “My Father and the Man in Black”

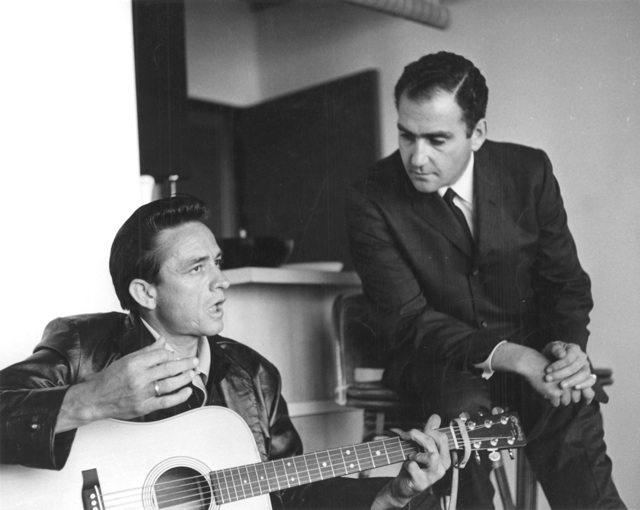

After his father’s suicide in 2005, Jonathan Holiff discovered a storage locker with audio diaries, newspaper clippings and memorabilia of his time managing Johnny Cash in the 1960s and 70s. Estranged from his father as a teenager, “My Father and the Man in Black”, tells the untold story of the talented and troubled Saul Holiff’s tumultuous relationship with Johnny Cash and a son’s attempt to reconcile himself with a father he never knew.

CB: How did your father (Saul) and Johnny Cash end up working together?

JH: My father was one of the first (if not the first) to bring Rock ‘n’ Roll to Canada. He booked Bill Haley and His Comets, Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly and other groups in the mid-1950s. But Saul was always looking for the next “big thing” and country was on the rise. So, in 1958, Saul booked a group called Johnny Cash and The Tennessee Two. Three years later, on a 10-date tour of Ontario, they hit it off—and Johnny asked Saul to become his manager. BTW: They had a hand-shake deal for 15 years!

CB: Did you get to understand your father a little better after reading and listening to all the correspondence between him and Johnny?

JH: Absolutely—but it was truly unexpected. It was my father’s audio diaries that made all the difference to me. The very first recording I heard was made in March 1966. My father was MY age when he recorded that tape. He was just a guy—not my dad.

Saul recorded an eyewitness account of the time Johnny overdosed in his motorhome the morning after his show at The O’Keefe Center in Toronto (just weeks after his arrest in El Paso). He said “I’m worried about whether Johnny was gonna make it.” He also said he was worried “about the baby.” It turned out I was 9-months-old on my first Johnny Cash tour.

But the point is, these candid audio diaries gave me the unprecedented opportunity to meet the man—not just the father.

CB: Was it emotionally difficult for you and your family exposing yourselves to all these things?

JH: Absolutely! Speaking for myself, I had to relive my father’s suicide a thousand times over the six years it took to make this film. The suicide is recreated at the top of the movie (my mother was there when Saul killed himself and was able to describe his death in great detail)—so I had to watch my father commit suicide over-and-over again while editing the picture. That was very difficult emotionally; so was listening to 60 hours of audio diaries recorded over four decades. But whatever pain it caused at the time has now been replaced with forgiveness and reconciliation. And I think my mother and brother feel the same way.

CB: How big of a challenge was it sourcing all the STOX and archives for the movie?

JH: HUGE. And it didn’t have to be. When it comes to stock footage, many filmmakers make broad requests such as “Any town USA, circa 1950.” After all, the quality of the footage is key—and that quality suffers when your needs become more specific.

Folks in London, Ontario (my home town!) were upset when “Walk The Line” misidentified the name of that Canadian city where Johnny proposed to June in 1968 (they even started a “write-in campaign” to 20th Century Fox to have it corrected for the DVD release!). So I made it my mission to locate only authentic stock footage of London, and other places where the Johnny-and-Saul story took place.

As for movie and television clips, this too was a big challenge. Given Johnny’s problems with drugs and alcohol in the mid-1960s—he was rarely seen on television between 1963 (“The Tonight Show”) and 1968 (CBC’s “The Legend of Johnny Cash”). Visuals from this period, of course, were critical to my story.

My father kept a record of all appearances—but few TV episodes had ever been released (when I wrote the movie). Fortunately, a 2006 visit to the Museum of Radio and Television in Beverly Hills (now The Paley Center for Media), allowed me to identify guest appearances and to confirm what my father noted in his audio diaries.

CB: What kind of reaction do you think your father might have, if he were alive to see the film?

JH: Before or after he killed me? Obviously, I’m being facetious. But I often tell people—particularly those well-meaning optimists who suggest my father left these materials for me to find after his death, that he would spin in his grave had he known I even touched his things—let alone made a movie about him. I wasn’t his favorite person.

Having said that, I like to think he would be proud of me—and happy to have had his story told. I didn’t know the man very well but, having quit Cash in 1973 and retired to Canada, he all-but-disappeared from the history books. I knew Saul well enough to know that—in the end—he would have been pleased to have been remembered for his accomplishments.

CB: Your father and Johnny had a real close relationship, what were some of the more fascinating things you learned about their relationship?

JH: It’s a long list, but the most fascinating thing I discovered about their relationship was how Saul influenced Johnny. Johnny was 29, Saul 38. Saul took on the role of Johnny’s mentor in the 1960s. Saul was very well-read, Johnny not-so-much (but he did read TIME Magazine every week!).

I believe Johnny’s esteem suffered a little at that time because of his lack of a formal education (his business letterhead was labelled “A few very rural, badly phrased but well-meant words from Johnny Cash.”). Indeed, he wrote more than once to Saul about not wanting to been seen “as a Hillbilly.”

When you read Johnny’s letters to Saul from that period, there are a number of times when Johnny asked Saul to define a word Saul had used in a previous letter (e.g. eunuch). Of course, Johnny soon became a voracious reader. But, in a letter to Saul in the 1970s, Johnny credits my father with helping him develop good reading habits.

CB: What are your feelings on Saul being overlooked in the film ‘Walk The Line’? He was a huge part of Johnny’s success.

JH: I am asked this question all the time—and I understand why. But the fact is, I never gave the issue a second thought. I was a talent agent in Hollywood for 18 years. I read The Hollywood Reporter every morning. I read about the movie going into production—and who had been cast. I knew they were telling the love story—so I didn’t expect my father would factor into that story.

Having said that, and this is the case with all biopics—“Walk The Line” carried the disclaimer “based on a true story.” Today’s audiences fail to realize just how much liberty writers take (e.g. June never appeared onstage, in the same city with Johnny until 196–when my father hired June for the show at The Big D in Dallas, Texas.

“My Father and The Man In Black,” on the other hand, is a documentary. It covers the same period as walk the line—but it all true! As a documentary, it has to be.

CB: Do you think this film will send out a message families who might have strained relationships?

JH: I know it will. I was fortunate to have started receiving letters from friends and acquaintances who read the script—telling me it made them realize they gave one child more attention than another (and some variations on that theme).

Now that we are playing film festivals—most audience questions are not about Johnny Cash but about family dysfunction. People see their own fathers and mothers in this story—and I’m thrilled. I set out, not to make a movie about Johnny cash, but to tell a universal story about fathers and sons. And I tell everyone I meet that they should make peace that parent now because they won’t discover a storage locker full of audio diaries after the fact! I am very grateful!

Latest Reviews

Trending

Tracks

Advertisement

Looking for something new to listen to?

Sign up to our all-new newsletter for top-notch reviews, news, videos and playlists.