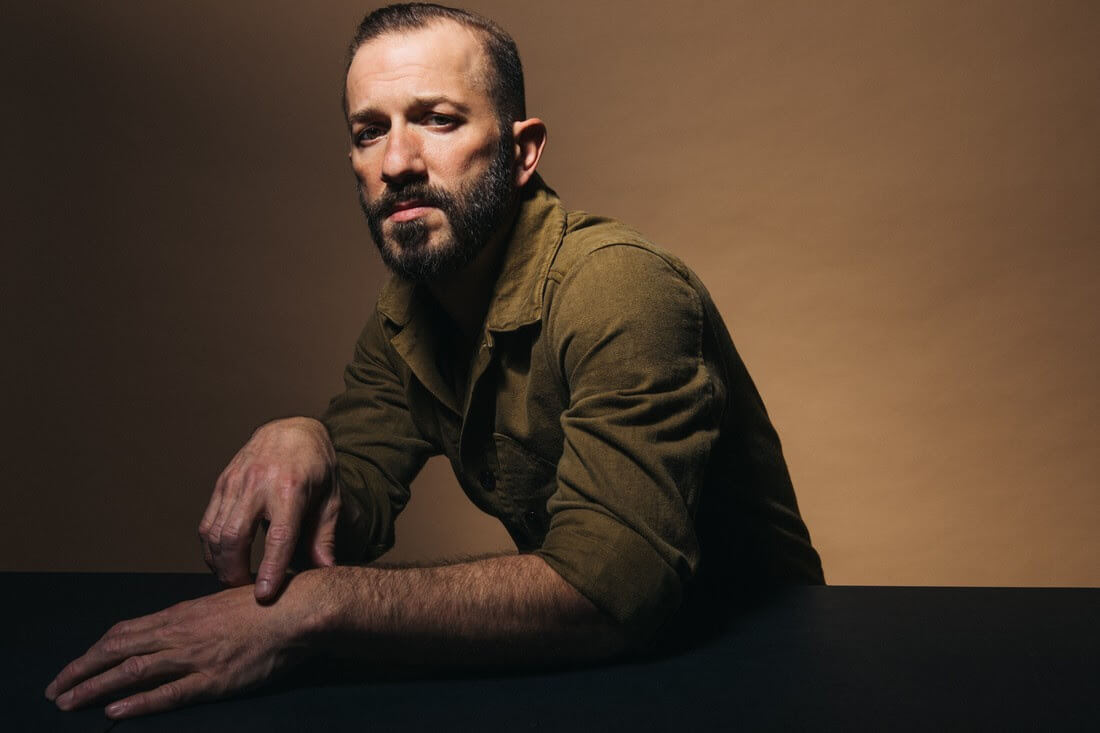

Colin Stetson Is A True Renaissance Man

Colin Stetson is a bit of a musical renaissance man. He’s played with some of the biggest names in rock/indie (LCD Soundsystem, Tom Waits, Arcade Fire, and many more), has scored a number of major Hollywood films (Hereditary, Texas Chainsaw Massacre, The Menu), and has even arranged a reimagined version of Henryck Gorecki’s Symphony no. 3. More than just that, his reputation rests on his intensely physical solo performances with his chosen instrument, the bass saxophone, an instrument few pick up and even fewer make a career out of. Below is a somewhat freewheeling chat with Colin that touches on spirituality, film scores, sci-fi, and more.

Northern Transmissions: My introduction to your work actually came with your reinterpretation of Gorecki’s third symphony. Did anything draw you to Gorecki specifically as a character, or was it purely the music?

Colin Stetson: Well, I was drawn to do that symphony when I first heard it. It when I was on tour with a band I had toured with many times. One of the things we did was a show and tell in the van, and that was one that came up late one night. Anyone who loves that piece’s first interaction with it—it’s a mystifying, deeply beautiful object. I’ve had a very personal relationship with it, and had wanted to do a version, a bit of an unconventional arrangement of sorts, since I was in my early-mid twenties. The opportunities weren’t entirely there back then…It got shelved for a while, and then things lined up all of a sudden in around 2015 to make it all come back and get finished.

NT: I feel like his music really fits with your solo work–it is minimal, but it isn’t so totally out there, it’s not atonal, it has structure. I saw he was considered part of this category of holy minimalists—I was curious if you think of your music as spiritual?

Colin: No. He was a hugely religious person. I know people make that distinction between religion and spiritual-ness. I know that was somebody for whom spirituality came part and parcel with his religion. I’m somebody who has never been either. I don’t use words like spiritual, because to me that word smuggles in a little of the God, the religiosity of old, of all these systems—those systems in that mode of thinking that goes back further than modern monotheism, of how we think of the unknown, higher powers. You trace it back, and monotheism came out of polytheism, came out of animism initially. There’s something about “spiritual” that I shy away from, even though if it was free of baggage it would be nice to say it. But conversationally it can lead to different notions of what is meant. I don’t think of my music as spiritual, I think of it largely as folk music, as storytelling, and on a visceral level an attempt to forcibly invite the listener into the present moment experientially. All of these things, being so fully aware of the present moment, it has become synonymous with what we’ve labeled “spiritual”, what we label the numinous. So I imagine the way I’d describe the experiential to some people might be interchangeable with the spiritual, but I would avoid it.

NT: I like the term folk music, I felt in those final big cathartic moments in Hereditary, the folk influence really came through and ushered it along beautifully. Separate question–I noticed a lot of recent stuff you’ve done has been related to space. Do you think there’s something that draws directors toward you when they’re making space films?

Colin: Let’s see, I’ve done The First, which was certainly space oriented, although we didn’t get our second season. Then the nasa doc I did for Disney was certainly space oriented. I would love to do more, what I’m looking forward to is a proper science fiction telling. We’ll see when that comes together. You know, I was a Star Wars kid, I was born in the seventies. Reagan shut the whole space program down, but when I was born we had recently gone to the moon, and I remember doing a book report about the whole plan NASA had, where by around 1998 they were going to have installed a biosphere on mars, that there were going to be people living and farming on it—they had a multi-part plan spanning into the 90s, but as part of Reagan’s reconfiguration that was scrapped, and now we’re just talking bout it forty years later which is an absurdity. I was very much in that headspace as a kid.

NT: Do you like horror movies?

Colin: I’m not a horror-file. If I have something like that it’s science fiction. But by and large I just like good things I haven’t seen before. Horror films are no different, now horror movies are a dime a dozen, and studios are hungry for cheap money. Horror movies are good or bad or neither, and in most cases they’re neither. In some cases they’re very good. My consumption of those things and adherence to those things is the same as my music consumption. I don’t have any genre affiliation, it’s just whether it speaks to me.

NT: There’s something very futuristic about your sound—I remember listening to one of your many soundtracks, and it sounded like a synth, but realized later it was your bass saxophone. Do you think there’s something about the merging of those, where it can sound almost totally computerized, from the future, but the fact that it’s an acoustic instrument gives it something else, something resonant?

Colin: For sure. There’s certain things that have become really ubiquitous—synths, strings used in particular ways for particular ends. You see certain imagery, you walk into a certain setting and you know what it’s gonna sound like since you’ve seen it already. Lots of stuff is done in that cookie cutter way, and most of the storytellers understand there’s a certain ethos, a way of doing things. And for me that’s the kiss of death, that’s the antithesis of actually doing good storytelling. But all that said, the function is still there. They might be doing something that’s been done a million times, and the audience might turn into a glass eyed zombie and let it happen, they go on autopilot, but at the same time there’s a certain function, these things work on some level, they elicit a certain response. I try to identify what that is, and figure out how to come in through the backdoor, to affect somebody in a way that is familiar enough to not alienate them, but unfamiliar enough to be captivating, something that keeps them on their toes, not feeling that they can just relax into it. There is a lot that can be done not just with the saxophones but all these instruments, and not just in the way you perform them and record them, that can emulate and suggest certain things that may have something more to do with synths, but ultimately you’re dealing with an acoustic instrument that’s being played by a breathing animal. It breathes, it is inconsistent, it is not a loop, there’s the sense of the natural going through it. It takes a lot longer to do something like that. Someone could do a synth patch in the fraction of the time it takes me to do the same thing with forty saxes and flutes—but ultimately the one that I come up with will not be possible. They are not identical offerings—one does one thing very well, and the other does quite another.

NT: When you’re approaching a score, how do you know when there needs to be silence?

Colin: Well, most of the time coming in the director and editor have done the heavy lifting where they want heavy music and not, and some places there are open times. But there are also moments when I hear something as music being a redundancy. How do I know? You watch things come before, what is music doing, is the emotion being furthered, is it coming across with just the acting or dialogue, and that’s just a call, a visceral, emotional call. I’ve had moments where directors were receptive, I’ve had moments where it hasn’t gone that way, I’ve had moments where everyone thought there should be a piece of music in a particular spot, then nearer the end we realized, how about watching without the music? It goes all different ways and depends on who you work with. Some people are entirely certain from the get go, and the idea of changing that is antithetical to their process, and there are those who really just like to tweak and tweak and tweak up to the end.

NT: A bit of a separate technical question for my own interest–I picked up bass in a band because we needed it, and realized how quickly lower registers can screw up a song if you do it just a little bit wrong. I’m curious–you’re a professional with decades of experience, but are there rules you’re following, or is it all sort of more embodied?

Colin: Rules is one of my favorite topics. The low end is a vulnerability, but if you know what it can do, it’s your strength. It can completely transform the character of a piece of music. All of a sudden, the low end comes in and defines everything else that happened in a certain way comes into play—it’s a compass, it defines everything up and down, it brings an order and a context to everything happening before it, and it can be very subversive, very transformative, and a hugely important tool. In terms of rules…I don’t really go for…my rule structures are all from situation to situation, project to project. If I’m doing a score, I want to make sure the score is as lean, focused, and doing as much as it can, with a clear character and aesthetic. You don’t look at it like a collection of scenes to micromanage—here’s a dramatic scene for drama so let’s use “dramatic music”, here’s a funny scene so be funny, etc. That’s just a Frankenstein, and that score has no defining characteristic. For me the first thing is establishing what the overall sonic character—what are the basic components, then playing within those rules, harmonically, the kinds of melodies if there are melodies, the kinds of instruments—very specifically, what goes and what doesn’t—if it’s everything goes, it’s not really conducive to innovation. You don’t search. It’s kind of that McKyver thing—you look around and find a few bits and pieces, and you have to figure out how to get out of the room with those bits, you have to think your way out, you can’t just unlock the door. That’s how I started doing what I do with the solo saxophone music. Simply put I just have that. If I use effects and loops and all that, I will not innovate, because I will look to outside sources to solve problems for me. If I don’t have that, if all I have is the horn and my body, then you have to figure out how to get around and through, look to the future, if I do this that and the other is it possible for this musically to happen. That’s how progress is made.

NT: Was that a definitive decision you made at music school, or did that evolve over time?

Colin: It was pretty solidly there, but it really calcified in my twenties, as I was playing more solo concerts, they were always done in that way. I avoided using pedals and electronics. It was a practice that was cultivated, then became by default defined. Then when I started to record the actual records, it was very much defined.

NT: I heard you were a serious athlete in college–may or may not be true, just saw online. To what extent do you think that sort of athletic suffering plays into your solo work?

Colin: High school not college, in college I was a practice machine. The athletics of music played into it in music school. It’s the same values–those who know what it is to kind of excruciate, to feel ecstatic in those spaces, to go into extremis, I had that at an early age, it became kind of baked into the DNA. To do that at 10, 11, 12, I really think chemically you’re imprinting that on a very deep level, so it ends up being how you relate to the world, to yourself. When I’m making music, the instrument I play primarily is a very physical instrument, it can be more or less so depending on approach. I “get off” more or less on the more physical approach to the instrument. I do, and always have, through the practice of interacting with the instrument, and sound production through that, those experiences that happen at the limit of ability. When you get into those—when you’re hanging by a thread, when you’re pushing through the known and into the unknown, that’s more or less my happy place, and it continues to be that. As I was discussing with a guy years back, there’s certain things that state imbues in music. I write certain music, even for scores, where I try to put myself in that position in order to make a certain kind of music for a particular scene, for a particular score even. Even if it’s something people aren’t seeing, it does imbue the music with a different quality. It’s like Berry Gordy in Motown transposing the songs up a couple steps so that the signers had to push into a bit of their range that isn’t necessarily possible so that they had to go for it, and going for it brought out that sense of uncertainty and passion. Putting us in those states in discomfort, or outside the realm of comfort, it’s more searching.

NT: I’m a competitive cyclist, where there’s kinda a cult around suffering, so I can empathize with that human in extremis bit. Last question: Favorite book you read this year?

Colin: Well, I just finished one I didn’t like at all and took me ages. I read Christopher Pauli’s To Sleep In A Sea of Stars, and that was a very fun read. Really imaginative storyteller, strong sci-fi conceptual mind, and writes in such a way that feels that you’re watching a movie, so there’s something popcorn to it, but there’s a depth to it, an emotionality to it, and the imagined worlds were really well done and quite fascinating. Then I recently reread Jim Harrison’s The River Swimmer, I tend to reread him in the fall. Something about tour always makes me feel like rereading Jim Harrison.

…

Stetson’s Favorite books: “Hard Boiled Wonderland and the End of the World. That’s my favorite. I’d also put True North by Jim Harrison, and Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy by Cixin Liu. That’s in my pantheon of favorites. That’s just the best hard sci-fi ever”.

Pre-order The Menu by Colin Stetson HERE

Latest Reviews

Tracks

Advertisement

Looking for something new to listen to?

Sign up to our all-new newsletter for top-notch reviews, news, videos and playlists.