Refracting the Future with Patrick Shiroishi

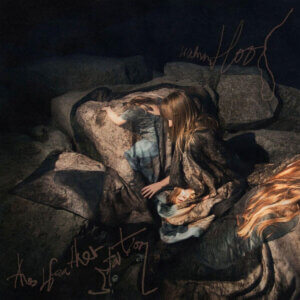

Patrick Shiroishi never takes a break. The Los Angeles multi-instrumentalist and composer has amassed a discography dozens of records deep, exploring jazz, noise, prog, ambient, and metal, armed with his saxophone and boundless curiosity. His newest release, Glass House, soundtracks a dance piece from Volta Collective, immersing audiences in provocative, sculpted choreography and the ambiguity of what “home” can mean.

Shiroishi’s score lives and breathes alongside the dancers. It stands on its own, using field recordings, strings, and saxophone to tell the same story. One can listen to Glass House and appreciate its pulsing emotion without knowing that it accompanies choreography, lights, and text. Ahead of Glass House’s release via Otherly Love Records, I caught up with Shiroishi for Northern Transmissions via Zoom to talk about multimedia, childhood, collaboration, and more.

Northern Transmissions: What are some of your formative memories of music, when you first became aware of it as something that you were passionate about and not just as something that was in the world?

Patrick Shiroishi: Music was always playing in my house. My mom would play classical and jazz [radio] stations in the car when I was growing up. I took piano lessons when I was like four. We did a “mommy & me” kind of thing. I continued piano and it was kind of always there. I don’t know what the impetus was, but I got a Walkman. I had the tape player with the radio. I didn’t have any tapes at that time, but I used it quite often for the radio. There was KROQ, which is the rock station here [in Los Angeles]. Power 106 was the bigger hip hop channel at the time. I tuned in all the time to those two. It gave me the realization that music is fucking cool. I liked the discovery of finding new artists and new music from an early stage. Getting CDs at Best Buy, going through the booklet, and living with it was always fun. That was the beginning. I think the curiousness never really left.

I also miss the specific sense of discovery that came with the radio or picking up a CD and being able to go through the booklet. The closest thing we have to that most of the time is the Bandcamp credits unless you buy a physical copy.

I’m still huge on the physical. I love the tangibility of it. I think it’s harder to wait till the entire record is out. If there’s an artist that I’m familiar with, I’ll try my best to wait until I get the whole thing. Sometimes it’s hard.

NT: When did you start writing music, beyond your curiosity and falling in love with it as a listener?

PS: That stuff was very late. I wanted it to be much earlier, but I couldn’t find people who were down to even start a band. I think it was my junior year of high school. This first band was called Otomoto. It was with three dear friends. We were a quartet: two guitars, two singers, bass, and I played drums. We kind of fucked around and did our best. I think there’s a really nice energy behind what we made. We started trying to make art rock, in the vein of Blonde Redhead and Deerhoof. Those were the first art rock bands I heard that weren’t on the radio. They changed my perception of what music could be. I guess there was screamo stuff, but I think some of that was derived from the internet, you know?

Later on in college, I found John Zorn and realized, “Oh, saxophone can make insane sounds, too. It’s not just for bebop.” I started playing in bands with saxophone in college and diving into weirder settings. We were more into punk jazz kind of stuff. Do you know Magma?

NT: The French band? Is that the Zeuhl band?

PS: Yes! I got heavily into Zeuhl, and then I joined a Zeuhl band, Corima. We have a new record. We recorded it so long ago, but we’re finally finishing it up.

NT: How would you connect the early music that you were making solo and with different bands to the music you’re making now? It’s been a continuum, but it’s hard to comprehend all at once.

PS: I still take from the same energy that I was taking from when I was in those earlier years. Energy is a huge thing. Even when I play quietly, there’s invisible energy I hope I’m giving off. I don’t know if I necessarily have my own voice on the saxophone yet, but I’m still curious. I still love finding new stuff. My music listening has expanded a lot since I was 17 or 16. My solo practice is the most important to me. That’s where I get to express and process what I’m going through. I don’t want to bring my baggage into the band setting. Having that as a vehicle has been nice and I’m glad I have that outlet.

NT: There’s been nonstop creation between your solo work and different groups. I think Glass House will be the tenth album that you’ve put out or played on this year. If I’m doing my math correctly, three of them, including the Sub Pop single, came out within the same two-week period in April. What is the draw of an ever-expanding approach, always exploring new sounds and playing with new people? There’s a certain deepening with a group like Fuubutsushi, where you’ve been playing together for years, but there are always new iterations with people that you haven’t played with before.

PS: I’m very lucky in the people that I collaborate with and the people who asked me to collaborate. Fuubutsushi has become a real brotherhood; I think it’s reflected in the music. There are bands that I’ve been part of for years, like Upsilon Acrux, which is more like a proggy thing. I see those guys a lot even when we’re not practicing, just at shows. I’ve known Dylan [Fujioka], who I play with in Upsilon, since high school. Being able to show each other new music and still play together and develop our vocabulary is special. Not everyone gets that.

It’s a joy to play with people not necessarily in the style or genre that I typically play in. That shit is always great because it forces you to think outside of your own box. How do I contribute something important to the music that we’re creating? A lot of times I’ll stumble on something while playing with someone else and think, “Oh, I should investigate this at home and see where that goes.” With my solo stuff, it varies a lot too. Descension was heavily processed with guitar pedals and there’s a lot of distortion. At that time, I was very angry, but it came from a love of experimental black metal. I was too young to hear silence is the opposite, just saxophone in a parking garage, purely acoustic.

Glass House is so different than silence, but for me, in a linear sense, it shows that I’m picking up on things that I was trying to work out years ago. I’m trying to release one solo record a year. I don’t think I’ll ever write a perfect record or achieve perfection. That shit is not that interesting to me. In the long span, it’s important to show and document what I was trying to explore and investigate that year.

NT: It takes a couple of years to internalize something inspiring. It might have been resonant or troubling, combined with whatever you’re exploring at the moment, and those things collide in the sound you make. You’ve previously worked within the dance idiom. What was that experience like? How did it prepare you for working on Glass House?

PS: Everything I’ve done before working with Volta was more improvisatory. I have a good buddy, Dean, who has a practice called Diagonal Studio. He makes sculptures that the musicians and dancers interact with and we get to improvise together. Sometimes we’re connected to each other, sometimes we’re connected to the wall. It’s another fun collaborative way to improvise.

Glass House was a little different; it was more structured. It was really great working with Mamie and the crew, she had a real vision. The music went through several iterations and she was a big collaborator in that. The first track has an art installation vibe. I wanted to give off a feeling of home, using a lot of sounds from my own home, from on the road, from hotel rooms. The second song has an actual beat they could move to. The piano piece, “the procession,” was something else entirely. It was cool having the dancers in mind, with all this information about the piece as a whole, and then incorporating my experiences of home into the music.

NT: Mamie mentioned that I was too young was what made her realize she wanted to work with you on this project, which is super interesting given how different they are musically. How did that artistic throughline establish itself, entering into the back-and-forth process of making this new piece, meeting her vision, and exploring the myth of home in your respective ways?

PS: It was fun. Initially, it was challenging because I wanted the music to ultimately support them. Mamie gave me space to improvise. There are parts live where I improvise, just saxophone. That didn’t make the record, but we started with that. She gave me a couple of reference points, where certain sections should have certain vibes. I took it home and tried to figure out how I could make it. I wrote most of it in December and January, when it was a slow time for musicians, being able to focus on what the piece is going to be, what sounds I could incorporate. Even though it’s a dance piece, I want the music to sound like a complete thought. Imagining what that’s going to be like, the music varied. Maybe each track is like a room in a house. If you listen from beginning to end, I think it narrates some sort of story.

NT: Overthinking the conceptual and multimedia aspects of a work, how they exist in conjunction and separately, almost betrays them individually. If you’re not worried too much about the other thing when you’re listening, you’ll hear that narrative in its own way without even knowing that it went hand-in-hand with a choreographed piece. How much did you think about making sure the music stands on its own while evoking the same themes that continue to inspire your solo work? What was the value of keeping that in mind?

PS: I’m approaching 40, which is insane, because mentally I think I’m still 25, you know? Where I’m at now, I can only be myself. Of course, I have thoughts of imposter syndrome and worry about trying to cater to listeners and sales. It’s so important for me to tell my story and my family’s story. A lot of that has come up in the past couple of years of releasing music. It makes the music the most honest. At the beginning, I was trying shit out and imitating people. In a way, you have to. It’s the chosen few who are original right off the bat, who can be a fucking true gem. I had to make that journey. I’ve been lucky to have been playing for so long, trying to talk about my experiences. I don’t think I’d be able to make music that isn’t that way.

Mamie was super gracious and was open to a bunch of ideas that let me be myself. Not everyone is like that, and it’s totally fine if you’re not — sometimes you have a fucking vision and it needs to be that. We did four shows in a row in February and March. It was awesome to see every night, everyone giving their all. I don’t know if I’ll ever play that again. It took a lot of money, energy, and time. It was a very special set of shows.

NT: That’s the ephemeral nature of a live performance. The experience will live with the people that got to see it and the rest is kind of invisible. In addition to being in conversation with dance and movement, with space and visuals, how did the script play a part? Three out of the four song titles come from the text. Unless you read the liner notes, you’ll take the titles as they are.

PS: Mamie’s partner Sammy [Loren] wrote it with Zoey [Greenwald] in conjunction. There was an actor who was speaking during some sections, which connected some of the music and dancing. Having the titles derived from the script was important to show how things were interlocked. Without the texts, it wouldn’t be the same. Without the music, it wouldn’t be the same. Without the dance, it wouldn’t be the same. That was my nod to them and the whole project.

This is one of the first multimedia projects that I’ve been a part of, with text, movement, and music. I was trying to figure out how the music would fit in and support, not taking up too much space. For example, it sounds like there are four sections to the final track. The second and fourth movements are more active than the first and third. During the first and third, it’s just a lot of held string chords — that’s when the actor was speaking to the audience. I wanted it to support but also create tension and a throughline of the whole thing. The B and D sections had a lot more movement and that’s for the dancers. I think it still works, even if the listener didn’t know all that. It was important for me to not fill all the fucking space.

NT: There’s almost creative dissonance between the motion and the music and how they things interact, finding the unity between them. Was that something that you felt as you were searching for the record’s sound, reacting and working with the dancers and representing that physicality in ways that you could, while also giving them the space to share their part of that story?

PS: It’s very important when you can use contradicting factors, like sound and silence or dissonance and harmony, even in a purely musical fashion. It makes for a super interesting combination or resolution. Maybe it’s because I listened to a lot of pop and rock when I was younger, but I love a nice fucking resolution. Maybe it’s cliché, but a lot of my records have that hopeful moment at the end. I’m pissed off about a lot of things. This country has a lot of ugly shit happening in it and it’s easy to be sucked into that death and doom. At the core of everything, there is hope that it’ll be better for the next generation, that we’ll be able to achieve something greater and more peaceful and more open.

NT: On some level, you have to have some hope or light, regardless of how subtle it is or what form it may take. The titular idea of a glass house is a space that should be sheltering you, but there isn’t the kind of solitude or privacy we seek in our homes. A lot of these ideas are things that you’ve explored, like childhood and family and how everything ripples through our lives and generations. I’m curious to hear you talk a little bit about how those themes melded together.

PS: When I was younger, I wanted to get out of the house a lot. Culturally, I didn’t want to be Japanese; I wanted to be white, so I could be “normal.” I think that’s something every kid goes through, this whole journey. Now I’m super proud to be Japanese. My grandparents went through a lot of shit. All of that informs me and my story. Learning about that for my solo practice is easy because I’m able to express all of these things. Having that space to process has been very important. All of that shit is ingrained in me and my sound. My hope is as I continue to play, it will continue to be there, helping shape whatever music I make.

It was a very familiar space for me while working with Volta and Mamie. The setting felt very natural. I didn’t feel strange or disadvantaged. It was very fluid. I had two months to complete the entire score. A lot of time when I make music, I write in bursts, but I can’t say, “It’s going to be a burst now!” I’m at the mercy of that. It kind of caught me at a wave, too. It was nice to be able to pull from all those things and inspirations and make music excavating similar territory. I’ve worked in this soil before, so I know what tools I can bring.

NT: Your music has taken on wildly different manifestations, from Fuubutsushi to your record with Claire Rousay to jazz trios to turning up on records by Agriculture and the Armed. Glass House still feels very unique and exploratory in a different way than usual, with how you compose, arrange, and perform. How did it come together in those two months?

PS: Over the past couple of years, I’ve been expanding more as a composer. When I write for myself, it’s very easy to do what I know. For the bands, we’re usually in a room and we’ll write together. I wrote a saxophone quartet to paper, which is a first. After seeing how the sound came from just fucking being on a page — I’m used to playing other people’s music, but having your own creation, I was like, “Oh, shit, this is fucking cool.” It’s a totally different way of creating. When I’m playing sax, my fingers naturally fall into patterns that I’m familiar with. Writing on paper and in different key signatures forced me to play differently and expand my voice.

With Glass House, I approached it that way and it was fun being able to compose for different instruments and sounds. The field recordings are the throughline of the whole record. Those sounds are equally as important as sounds created by instruments. That also plays into my curiosity. There are so many ways to make sounds and music. It’s all music.

NT: Even the things that we wouldn’t label “music” within a capitalistic society still are music. This reminds me of Lia Kohl’s record [that you played on]. The sound a card reader makes is just a synthesizer. Someone composed that. We think about them as bothersome, but it’s still part of the music overwhelming us all the time.

In Japan, there are little ten-second jingles for each train stop. For the casual person, it’s a fucking jingle. Hiroshi Yoshimura made a good amount of them. That fucking blew my mind. Such an influential composer was making sounds for everyday use. I think that’s a beautiful thing. Lia does such a fucking great job of capturing that, too.

NT: As someone who’s always letting your curiosity guide you, whether it’s solo or with a dance company or any other iteration, what is your relationship with the unknown? It’s all-consuming and it’s always going to be there since we can’t possibly know everything, but if you remain curious, you’re always looking to shine light on different parts of the unknown and make it known to you, inasmuch as one can even know something.

PS: There’s just so much out there. This summer, I got obsessed with city pop. I’m fucking Japanese! I don’t why it took 37 fucking years of my life to find it. I asked my mom and she knew all about it. There was this whole world that I wasn’t privy to. There are so many connecting dots. It’s wonderful and beautiful, and sometimes it’s overwhelming. I want to know what’s happening now and what’s happening with the new generation. Sometimes I miss stuff that my friends put out. I wish there was more time in the day to listen to stuff. That’s just music, film is another full fucking thing! And goddamn, I have so many books.

I’m really glad that these art forms exist. Even if 10 people listen to Glass Houe, that’s fucking incredible at the end of the day. People took the time to dive in. There’s still a lot of new music, styles, and techniques that are waiting to be discovered and tapped into it. That’s fucking exciting, you know?

NT: It’s all intersectional and I hope we never let it stop blowing our minds over and over again. Through the process of making this record, what’s something that you feel like you learned about your own art, something that came to the forefront and revealed itself?

PS: It touched on how I want to compose more for other instruments. I want to do another [sax quartet], but that’s very in my wheelhouse. Writing for Glass House, having the string parts and different weird acoustic sounds, was very cool to hear. I finished this commission recently for a string sextet. Chris [Jusell] from Fuubutsushi was gracious enough to lend his time and gave me a lot of notes. I want to write for an orchestra or weird small ensembles. The downside is that it takes a lot of time to write and find people to perform it. I was lucky that Wild Up played the saxophone quartet. They’re going to play the string sextet, too.

NT: I like to pose this last question to pretty much anyone I talk to: what’s something you love about your own art and creative approach?

PS: My music comes from a place of honesty. I feel like I’m on a path to finding who I am at the end of all the music. Even if it’s something like a guest spot on Agriculture’s album, I am very lucky to have played on records in so many different genres, whether it’s rock, ambient, or black metal. All of these things are things that I’m interested in — I’m obsessed with music. I am a music lover first, then a performer. Through being in the scene and playing for all these years, I’ve been able to find myself. Without music, I’d be a totally different person. It helped me be who I am today. It’s like a cycle, life and music and being able to express myself. I’m proud of what I’ve been able to create. I hope that I’m proud at the end of the whole journey and I try to let that be the guiding light of everything.

order Glass House by Patrick Shiroishi HERE

Latest Reviews

Tracks

Related

Sorry, we couldn't find any posts. Please try a different search.

Advertisement

Looking for something new to listen to?

Sign up to our all-new newsletter for top-notch reviews, news, videos and playlists.