Interview with Andy Gill from Gang Of Four

Andy Gill has been playing guitar for the Gang of Four for nearly forty years. Throughout that time he has seen music, technology, and people evolve, and weathered various personnel changes within the group that he started in 1977. At the time that I Skype with him in London, he is the sole original member.

With a new live album recorded at Islington Assembly Hall in London during the tour for last year’s What Happens Next, Mr. Gill is, as always, firmly rooted in the present. Content with relatively new vocal collaborator Gaoler, and relishing the opportunity to collaborate with others, he seems happy to reflect on both the history and future of his band. But ultimately, he is still devoted to an approach he formulated as a young musician. His tendency towards an outward-looking, critical perspective remains intact, which is reflected in his new music as much as his conversation.

Northern Transmissions: Thanks for joining me today, it’s an honour to speak with you. How are you?

Andy Gill: Good, thanks, not a problem. I’ve been doing quite a lot of talking recently, but it’s all good.

NT: Ok great, I’ll start going through some of the questions I have for you then. Since you started with the Gang of Four in 1977 through to the present time, which has been nearly forty years, the Gang of Four has become a Gang of One. What does it mean to you to be the last man standing?

AG: Well, I think I go about the process of making songs, making sounds, asking personal questions, and trying to turn things around in an imaginative way in much the same way now as I did then, and all of the years in between. I mean, there’s different people around me, and Jon King was my most long-standing partner, but there have been different people around me through all the years.

NT: Right, I mean you worked with a number of interesting musicians on Gang of Four’s last album What Happens Next, including Allison Mosshart (The Kills) and Robbie Furze (The Big Pink), so you are still in a collaborative mode. Are there other artists that you would interested in collaborating with on future projects?

AG: When I started What Happens Next I didn’t really have a clue what I was doing. I just pushed the boat out and started out trying to do one or two things, tried to do crazy things, and then I thought ‘Oh, I need a vocalist as well’. I always liked the idea of working with some of these people that I knew. Allison and I had met a few times and I had produced her in studio for a while, so I knew her. Herbert Gronemeyer is an old friend really, of probably twenty years. I’ve just really been enjoying the freedom to do that. In terms of going forward, I’ve got a bunch of songs that I’m demoing and hoping to get out early next year. I really enjoy working with Gaoler (John Sterry). That’s not to say that I would rule out working with anyone else, I just really enjoy working with him.

NT: That brings me to another question about collaboration: How do you approach producing other artists? Do you like to be really involved with the process, or do you like to step back and help bring about the artist’s vision?

AG: Sadly, very much the former. I say sadly because I think it puts quite a burden on you as a producer if you like to get involved- if you say, ok, you want me as producer because of what I’ve done on my own records and you want to bring some of that methodology to what you are doing. So, I do tend to suggest quite a lot of changes. I like to get into the studio and go through the songs and say ‘Why is this bit like this?’, and very often it’s just so they have to explain it to me, because it really works. Or I might say ‘this beat is really busy and clunky, why don’t you just simplify this beat and make it a bit funkier or something?’ Which is actually what I do with my own stuff. Sometimes I think you do yourself and everybody else a favour if you just back off a bit.

NT: Yeah, try to maintain a kind of objectivity. Could you talk a little bit about the credit that Frank Ocean has given Gang of Four on his album Blonde?

AG: What happened was I got an e-mail from his manager Wendy, and she said ‘Frank is interested in using something from “Love like Anthrax”’ which was quite intriguing. I said ‘Yeah, that shouldn’t be a problem, is there something I can hear?’ She called me a couple of days later, and I was on a tour bus somewhere in California. She played it on the phone to me, and to be honest I couldn’t really hear it properly. But I just said ‘Whatever, I like Frank Ocean, go for it’. And also, I guess Frank Ocean is quite a big star, really. A lot of people wouldn’t bother asking, they would just kind of use it, or disguise it, or do their own version of it. So I respected the fact that permission was requested.

NT: Have you had those kind of requests before, to use your music?

AG: In terms of being used in somebody else’s stuff, not really. I’ve had funny conversations with people. A few years ago I was in a hotel in Glasgow, and Massive Attack were in the same hotel. We all bumped into each other at the bar, and they were just kind of apologizing about some of the things they had pinched from Gang of Four. It made me sort of think because there’s a part of their style, and a part of the Bristol sound, with that sort of side-stick click, that comes from “Paralyzed”, a song I wrote for Sonic Gold. Also, I ran into Flea a few years ago at a launch party for a Damian Hirst exhibition, and he said ‘Thanks Andy, for not suing us’. There’s still time!

NT: That’s true, you could still do it!

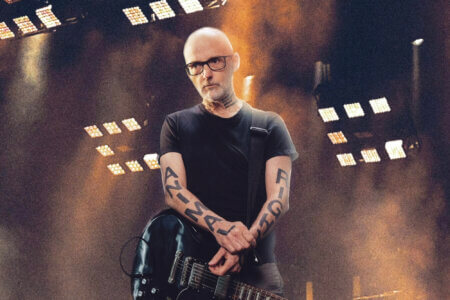

AG: Actually, talking of that… Moby. There’s a song of his on that big album called… “Bodyrock”? That is actually from Gang of Four’s “What We All Want”, it’s the guitar riff. That’s what it is, actually, and I keep meaning to bring that up with young Moby.

NT: I’m assuming no permission was granted?

AG: No permission was requested.

NT: Yeah, I mean it might be worth bringing up with him at some point.

AG: Well, yes he said something like ‘I was a massive fan, and it was my homage to Andy and the band…’ and well, ok, but all them millions of dollars went straight in your pocket.

NT: Yeah, that was a huge album. Gang of Four has always been a politically driven project, and you were outspoken towards the neo-liberal ideology that took over England in the 1980s. How has the current political climate in the United Kingdom, in light of events like Brexit or the seeming collapse of the labour party, affected the music that you are currently producing?

AG: On What Happens Next there is a song called “What the Nightingale Sings”. It could have been written about Brexit. It’s about people imagining a golden age where they are all racially similar and hold the same views, and everybody knows each other, and it’s kind of located in a nostalgic, golden-lit countryside. A rural idyllic paradise. And that’s kind of contrasted with the nasty cities, where people are supposed to be all alienated and don’t know each other. As I say, it could have been written about Brexit. I mean it’s very significant that London itself, London and Scotland, were the huge exceptions and all voted Bremain. It was the countryside. It was, bizarrely, the Welsh farmers and the people from the leafy suburbs that all voted the Brexit way.

NT: How do you see the role of music during times of political turmoil or unrest? It does seem to be kind of a trend around the world right now. So what role do you see music playing in the part of the world that you live in, or other parts of the world?

AG: Obviously, Gang of Four always has a questioning approach. It was always trying to find new, appropriate musical and lyrical languages to deal with the world around you as you saw it. I’m not sure many people really take that approach. I would like to hear about stuff if it was there.

NT: I’m asking because it seems to me that there is a reluctance on the part of a lot of musicians to get too involved with putting out an opinion like that. So I was just wondering if you felt that the role of music had changed since you began. Do you feel like there were more people interested in speaking out for what they believed in when you were starting out?

AG: Well, classic punk rock from ’76, ’77, whether it’s the Ramones or the Sex Pistols or whatever, wasn’t political in any particularly meaningful way. It was more of a reaction to the incredibly self-satisfied music establishment and the pervasive laziness that went throughout the music world. It was a great shot in the arm in that regard. People think of the Clash as being a political band, but I’m not sure if I see that. Somebody from Northern Ireland sent me a clip of Joe Strummer doing an interview, and people were asking him about Gang of Four, and he said ‘Gang of Four is fine. The problem is that they don’t know how to sugar the pill’. So basically what he’s saying is that the Clash had some kind of message or some hard-to-take content which they knew how to encase in some attractive musical form- with the implication that the Gang of Four didn’t. It’s an interesting clip.

NT: You are known as an innovative guitar player, bringing together disparate influences from the time you started- hip-hop, dub, punk, etc. How has your relationship to the instrument itself endured, and do you see much innovation with the instrument in today’s musical climate?

AG: On the last point first, I think St. Vincent’s great, and she was very flattering about my guitar playing. I think she’s got a pretty innovative style. I mean she’s a proper, trained musician, unlike me. She knows what a diminished fourth is, and sadly I don’t. But I like her guitar playing quite a lot. When I’m trying to construct a song, to me, the instrument is the band. Because if you play a lot of Gang of Four guitar parts on their own- you can’t play them on their own. You could try, but it would sound nonsensical. It only exists within the context of the bass and the drums and the chanting and the vocals. It’s like the songs are performed by this instrument called the band.

NT: Getting back to influence, do you feel flattered when you hear your musical approach echoed in contemporary bands? Can you think of anybody who has expanded on your ideas in a way that you really appreciate?

AG: Well, yes- Massive Attack. I’m not exactly a huge fan of all of the Chili Pepper’s work, but I think every now and then they do great stuff. The Futureheads- it’s sad that the Futureheads didn’t keep going. They loved the Gang of Four, I liked what they did a lot, and I produced them. I often hear bits and pieces of songs and think ‘that’s kind of Gang of Four-ish’, and I like a lot of that stuff.

NT: A Canadian band that bears some of your influence, formerly known as Viet Cong, now known as Preoccupations, encountered a lot of controversy in this country and abroad over their name, which they recently changed. You defended their right to use the name. Do you believe that the change was a positive outcome? How do you see how that played out?

AG: Well, they were under a lot of pressure and it must have just been annoying for them. I can’t speak for them, but I’m guessing they must have just thought ‘We’re going to be hounded forever, and we just want to get on with our music’, is what I would imagine. I still don’t quite understand what the big problem was. Maybe you understand and can explain it to me?

NT: I think there were a few different strands of offence that were taken to the name.

AG: Ok, well give me the most plausible one.

NT: I think the one that was most plausible was that they had used it as white men…

AG: Ah, so cultural appropriation?

NT: Yeah, it was seen as a use of something that wasn’t theirs, and that was traumatic for people who had been through the war.

AG: Well, my question would be, if they called themselves The United States Military, would that be fine? Because they’ve done a bunch of stuff, with napalm and… there’s two sides to that war. No, I mean you gave it a good shot there but nah, no. And I have absolutely no truck whatsoever with this cultural appropriation thing. It’s what makes the world go round, it’s what makes the world an exciting place, and it’s how cultures learn from each other. What are we going to say if someone in New York steps into a sushi restaurant? Is that culturally appropriating Japanese food? I’m really struggling with that. All of American music is culturally appropriating other music. That’s the way it works. That was always the whole point with Gang of Four, that it was four white guys from Northern England naming themselves after these cultural revolutionaries who were on trial in China. The point of it was the absurdity. That whole criticism is so lacking in imagination and po-faced.

NT: Do you believe that this is a good time to be a musician?

AG: No. I mean part of the problem is the whole financial state of everything. I mean basically what happened was everybody was file-sharing like crazy so normal sales kind of disappeared. The streaming companies came along and said ‘Well, you’re earning nothing, but we’ll pay you a little bit’. You get paid pennies. It’s difficult for people to make any money. People will say ‘The live thing’s ok’ but, no. It’s needy times for musicians, that’s for sure.

NT: Do you see any positive side to the changes technology has brought to the industry?

AG: The easy answer in a way is that now people can make music on their mobile phone or laptop, and that’s got to be a good thing because it’s enabling everybody, but that’s the easy answer. Back when we started we worked together to make a song, and worked together with people to learn how to play it and rehearse it. It was based on figuring things out in the rehearsal room, not the laptop. Then we had to figure out how to record it, which wasn’t always easy. When the piano was invented that changed music permanently. Whether that made music before the piano less good or less interesting or whether it necessarily became better or not is moot point really. History is full of technological advances that change the way we go about music and do radically change the musical form itself. So with laptops, there is much more of an emphasis on electronic music.

NT: You’re releasing a live album of the show that you played at Islington Assembly Hall in London last year. What prompted the decision to produce a live record, and one of that show in particular?

AG: The band has only ever released one live record before- from the mid-eighties when Gang of Four had our first break. So we had been touring a lot, and I thought it was sounding really good. On tour we play songs from every album. So I liked the fact that it is a performance that embraces different eras and times, right from Entertainment to What Happens Next. We just happened to record that gig. They have a lot of in-house recording stuff. There was a little bit of editing because some songs have sections that live are a bit longer, and I just shortened those to fit on the record. None of Gaoler’s vocals are anything other than what he sang that night. I had to re-do a couple of mine because they were woefully out of tune. It’s kind of like a best of, and I’m really pleased with it.

NT: How have you seen audiences change and react to Gang of Four over the years?

AG: When we started it was mostly a young audience. As we’ve gone on, that part of the audience has aged in sync. The interesting thing is how many younger people turn up. That could be to do with the Bloc-Party’s and Franz Ferdinand’s and Futurehead’s. But fifty percent of the Gang of Four audience is under twenty-five. And it’s quite interesting to see how the younger generations have gotten into it as we’ve gone along.

interview by Dan Geddes

Latest Reviews

Tracks

Advertisement

Looking for something new to listen to?

Sign up to our all-new newsletter for top-notch reviews, news, videos and playlists.